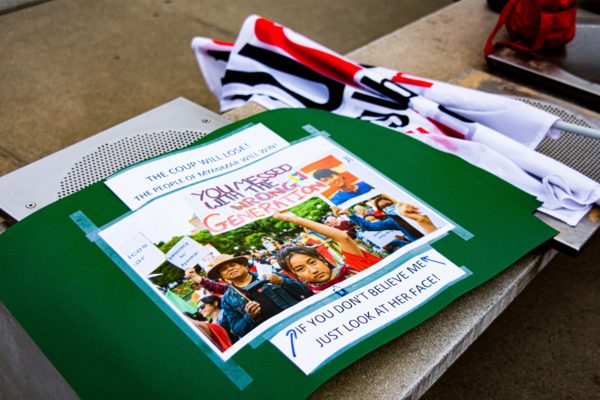

(Protest Signs/IndustriALL Global Union/Flickr)

by Ellen Goldstein

As protesters laid siege to the US capitol last month, many wondered whether the United States’ imperfect democracy would survive. “Democracy has prevailed,” US President Joe Biden said in his inaugural address, and indeed it has for now. Myanmar has not been as fortunate, facing a coup on February 1, 2021 when Myanmar’s armed forces seized power. However, the strengthened voice of civil society and a new generation of activists will determine how the next steps unfold.

Myanmar’s military, represented by the Union Solidarity and Development Party, fared particularly badly in the country’s recent election, and staged a coup rather than allow the new parliament to be seated. Myanmar’s government leader, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, and her team were arrested. A one-year state of emergency has been declared and power transferred to Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. In Myanmar, democracy has not prevailed.

This is a moment of deep fear for many in Myanmar. For those in the older generation, it is not fear for their safety, but fear of democratic backsliding. Can it go back, all the way back, to the bad old days of authoritarianism and extreme penury and total isolation? Is this a return to the days of censorship and government informants in every tea shop?

In Myanmar, the question is whether today’s resistance to the coup is just a repeat of the 1988 uprisings. Those protests made Aung San Suu Kyi a national democracy icon, but were brutally crushed by the military, sending many protestors to prison. Or, is it possible that democracy will prevail this time?

As resistance to the coup mounts in Myanmar, it is becoming clear that this is not 1988. The protestors today have come of age in a relatively open society. They are worldly, technologically savvy, and unafraid to speak out. They are unencumbered by their parents’ fear of brutal repression. They are bold and even bawdy, dancing and chanting and hurling expletives against the coup for local and global audiences. They are today’s protestors and—many would wager—tomorrow’s leaders.

The young protestors have thrown away the playbook from 1988, and so should we in the international community. We should lend our voices and our support to the protestors and to the network of civil society organizations on the ground in Myanmar. We should—as the Biden administration has rightly concluded—intensify targeted sanctions against military leaders and enterprises. We should also avoid disengaging from Myanmar and imposing general economic sanctions, as proposed by some human rights advocates. This latter idea comes straight from the 1988 playbook. It served no purpose other than to hurt poor households and deepen the country’s isolation, while playing into the hands of corrupt military oligarchs. It did not work then, and it will not help Myanmar now. Actively engaging with and supporting voices on the ground, rather than turning away, will be the more effective route.

It is not 1988, nor even 2011, the year the Myanmar military, the Tatmadaw, launched a transition toward democracy that allowed Aung San Suu Kyi to come to power. For those ten years from 2011 to 2021’s coup, Myanmar was not much of a democracy. The country settled into an uneasy power-sharing arrangement that granted Aung San Suu Kyi circumscribed powers, left the military’s control over national security intact, and preserved a shadowy network of economic interests.

Despite shortcomings, ten years of democracy—or at least a path toward democracy—has been good for Myanmar, and the positive changes have become difficult to completely undo. Prior to 2011, the military dictatorship had spent the previous fifty years running the country into the ground. Myanmar had once been one of Asia’s richest countries, but entered the twenty-first century as one of the poorest, with more than half the population in extreme poverty, enduring widespread malnutrition and illiteracy. Since 2011, the transition toward democracy and an open society has made Myanmar one of the world’s fastest growing countries. Poverty has fallen by nearly 50 percent. Access to electricity rose from just one-quarter to more than half the population. Opening the telecommunications market has allowed 90 percent of a previously information-starved populace to own a smart phone. People are connected to each other and to the rest of the world. Censorship has been abolished, and a freer press has emerged. State institutions have been modernized and civil servants empowered. Notably, an estimated ten thousand civil society organizations have emerged from the dark past, amplifying the voices of Myanmar’s diverse people.

Five decades of repressive military rule prohibited the development of civil society organizations. Since 2011, along with gradual modernization of government institutions has come the fledgling development of civil society, first in the form of humanitarian organizations to cope with natural disasters. Today, the country has a broader network of civil society organizations focused on economic, social, and political issues. Civil society groups have been formed not only in the Burmese center of the country, but also in minority-dominated border states where they often provide public services in lieu of the government. This empowerment of citizens’ voices will make it more difficult for the military to tighten its grip and undo the progress of the last ten years.

Democracy has been good for Myanmar, but not everybody has benefitted. This partial democracy has been deeply flawed, with continued conflict, repression, and systemic discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities who make up an estimated 30 percent of the population. Discrimination is ingrained in society, and brutally enforced by the military. One in five people in Myanmar lack identity papers and/or full citizenship rights. No people have suffered more than the Rohingya, victims of crimes against humanity and forced displacement perpetrated by the military. Through their suffering, Aung San Suu Kyi’s failings as a democratic leader were exposed to the world.

Instead of a liberal and tolerant democracy, Myanmar became an increasingly illiberal and intolerant one that reinforced ethnic Bamar domination and perpetuated a cycle of conflict and repression of ethnic minorities. In the wake of the coup, the military junta claims it will return Myanmar to a democracy within a year. Whether and in what way this occurs depends on the strength of civil society, the courage of these youthful protestors, and their commitment to a democracy that is liberal and tolerant, strengthened by Myanmar’s ethnic and religious diversity.

Given the balance of powers inside and outside Myanmar, the Tatmadaw is unlikely to reverse itself, accept the electoral outcome, or restore Aung San Suu Kyi to power. However, the military will not be able to crush today’s protests as they did in 1988. Today, ten years of global engagement in the context of a more open Myanmar has nurtured civil society and brought forth these young protestors. The future of Myanmar’s democracy depends on them—let us be there for them this time.

Ellen Goldstein is a PTF adviser, and consulted on the most recent PTF project in Myanmar, the PEACE Project. She is also the former director of the World Bank in Myanmar, and is currently writing a memoir about the experience. You can follow her on Twitter @EllenAGoldstein.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of PTF.